June 4, 1989

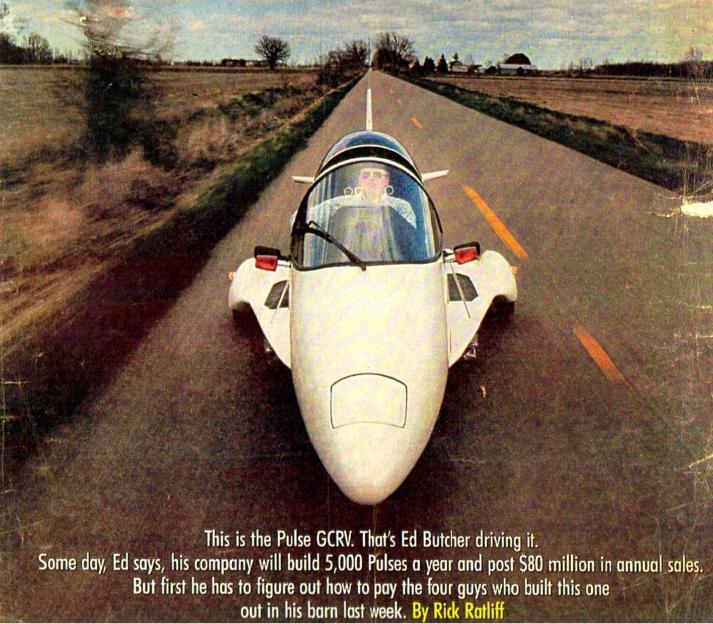

In the glow of a late afternoon, the most bullheaded man in Shiawassee County strides to his pole barn and slides open the door. Inside, among the power tools, parts bins, pin-up calendars and welding torches, Ed Butcher confronts a glossy contraption that looks like an F-16 without wings. It's pointed right at him.

Blood red, the length of a small sports car and the width of a cruise missile, this machine is called a Pulse GCRV, for Ground Cruising Recreational Vehicle and despite appearance, it isn't nuclear-armed or jet-powered. It is, in fact, a curious cross between an automobile and a motorcycle.

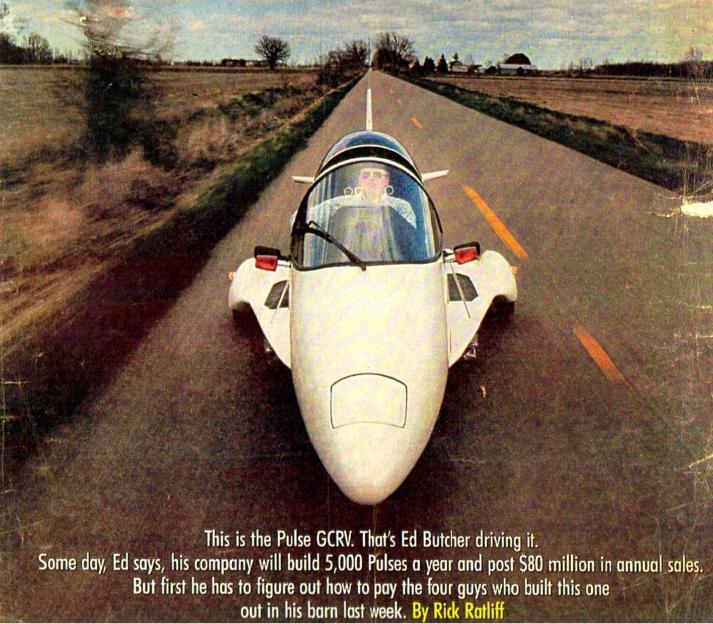

It is powered by a rear-mounted, four cylinder Honda motorcycle engine and transmission mounted on a steel frame within a fiberglass body. Only three of the Pulse's four tires touch the ground at a time; two are 8-inch trailer tires that protrude from stubby outriggers mounted on either side of the body. Beneath a sliding glass canopy, the Pulse accomodates two people--barely -- on seats designed for power boats. The passenger's legs must straddle the driver's seat in front.

This is no one-of-a-kind custom job; it is the 328th Pulse. It reflects the tempered-steel will of Butcher, president of the Owosso Motor Car Company, and a full week of sweat by four resourceful men in their 20s who built it in this barn, as they have so many before, largely with parts bought at local car dealerships, motorcycle shops and hardware stores.

Those men are gone for the day, they have their farms to work.

Butcher, alone with a visitor, climbs into the virgin Pulse and turns the key to fire it up. In addition to being Owosso's president and chief salesmam, Butcher is its most rigorous test driver. He likes to put 100 miles on each Pulse personally before handing it over to a buyer.

What Butcher runs is either the smallest auto company in Michigan or the second-biggest motorcycle manufacturer in the United States. In fact, Owosso Motor Car Co. is technically neither, because the Pulse is legally classified as an autocycle for registration purposes by the Michigan Department of State.

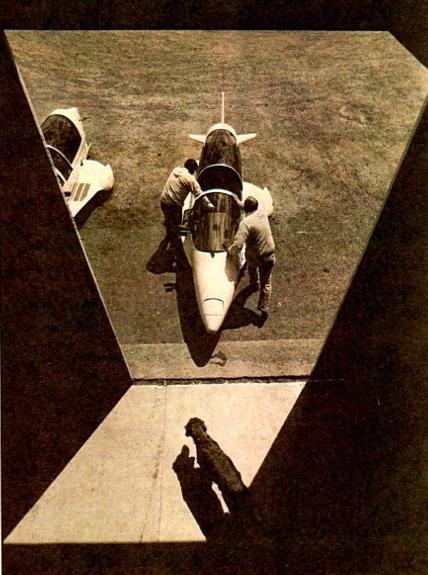

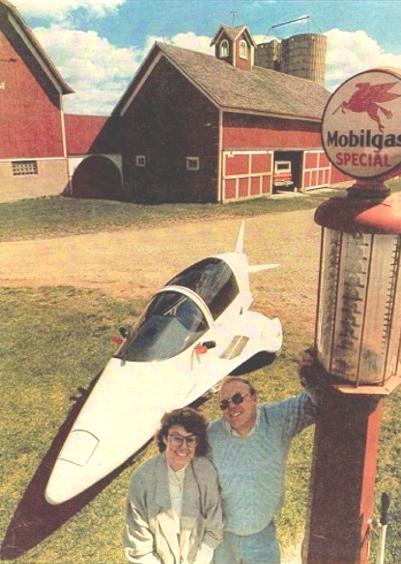

It isn't everyday that you find an auto plant in a pole barn. But little about the Owosso Motor Car Co. is common. And rarely has such a high-tech product emerged from such a down-home setting. The pole barn is next to Butcher's blue-gray ranch house, on a corner of his 160-acre farm and is just down the road from the spreads of his parents and in-laws. The factory floor occasionally competes for space with Butcher's combine. Heat in winter comes from a wood-burning stove. The hayloft serves as an office for Butcher, 42, and his long-suffering wife, Sue, also 42.

Their sons, Steven, 18, and Brad, 16, helped around the barn and factory. Their daughter, Lezlie, was studying graphic arts at Rochester Institute of Technology in New York, and would come home between semesters to paint pinstripes. Ed Butcher's cousin, Larry Butcher, helped assemble the cars. Sue Butcher kept the books and typed letters with her head bent beneath the loft's low, slanted ceiling.

If at times Owosso Motor Car seems like a quirky Greenfield Village (Dearborn, MI) throwback, or a hobby run amok, be assured it is not only a serious business but a scary one in which substantial sums are routinely at risk.

But Butcher has been blessed -- or cursed -- with an inability to leave unfinished anything he starts. "He always liked to keep at things until he got them just the way he wanted, " recalls his mother, Dorothy Butcher. Young Ed once spent many days building a miniture crane with whittled sticks, even perfecting a trip release for the bucket, which he fashioned from a tin can.

Now, splashing through the muddy puddles of the gravel driveway, past half a dozen other Pulses needing service scattered on the grass. Butcher negotiates the red Pulse's fiberglass snout around the potholes that dot Six Mile Creek Road. He pauses to zip his tan fishing jacket against the wind.

Butcher squirms his ample, bejeaned bottom on the optional tan leather seat and sets his suede saddle shoes gently against the pedals. His right hand curls around the gear shift and his left hand grips the thick steering wheel.

A little gas, a slip of the clutch, and he is off, curly red hair dancing on his balding crown. Slowly at first, he guides the Pulse between the wheat and soybean fields, past the erect Italianate farmhouses and the tidy barns proudly emblazoned with the names of their owners. Past the cows, horses and chickens, past farmers who nod and wave as if he is chugging by on a tractor.

Then, after letting the car idle a bit beneath a maple tree canopy, he lets her rip. The guttural howl scares the birds away, and the acceleration is astonishing: Zero to 60 in 6 1/2 seconds. That's Corvette territory. Not bad for a $15,000 car that gets 76 mpg and costs as little to insure as a motorcycle.

Corn stubble on either side of the road flies by in a smear as the speedometer edges past 75 mph, the tautly sprung Pulse thudding in the ruts Butcher can't avoid.

Butcher routinely drives 100 m.p.h. in his tests, but isn't convinced that #328 can handle that kind of speed just yet. "The brakes need bleeding. The left outrigger wheel needs its bearings repacked. This new, taller canopy results in a dash configuration that hides several gauges behind the steering wheel. The dashboard has to be redone. There's another day or two of work ahead.

I'd say this is going to be a good one," Butcher said while strutting to the house, his family and a good hot meal -- the illusory trappings of security.

THE NEXT MORNING, the sealant still clings annoyingly to Butcher's jacket and hands. Butcher is on the phone, his face crushed against the receiver, listening to his banker explain that the woman who put down a $2,000 deposit to buy the red car did it with a rubber check. A current drain created by the power tools makes the lights flicker in the loft office.

Normally, says Butcher, he wouldn't accept anything but cash or a certified check as a deposit; even then, he would wait for the check to clear before building a car. But this woman had seemed so honest, and she wanted her car right away. So they took the chance.

She had flown out here some weeks ago with her boyfriend, driven a Pulse, poured five gallons of thick praise over it, then consulted her date book. Yes indeed, she noted, the certicicate of deposit matures in two weeks. She had shaken Ed Butcher's hand with the conviction of a preacher as she handed him the check.

Now he recalls the woman who seemed so interested just a few weeks earlier. She said she even wanted to be a dealer. The woman who said she wanted half a dozen cars. Butcher listened as she explains hoarsely that she is under a doctor's care, that she is deathly ill, and that she can't take the car, any car.

There's no point in arguing, so Butcher hangs up, his face grim. He already has $50,000 in bad checks languishing in the company safe. Heres one more to keep them company.

I call the lady, and she's crying," says Butcher. "I've seen all the tricks, but I thought I knew this one was for real. Now in the next day or so, I have to make some fast decisions.

"I guess something tragic has happened in this woman's life. Unfortunately, my financial situation doesn't leave any room for my customer's tragedies."

Butcher is an ex-Marine reservist and the adopted son of a bulldozer operator and farmer. The farm life that gave Butcher his stubborn streak also gave him the inclination to leave his doors unlocked. Maybe Ed Butcher is a bit too trusting.

And Butcher says about his car, "People don't opt for a Pulse instead of an Oldsmobile. The chief competition for the car comes from fur coats, diamond brooches and cigarette boats." If Ed Butcher made sofa beds or lawn tractors or kerosene heaters, he would not have the problems he does.

Prospective buyers wearing custom-made clothes arrived at his pole barn in rented Lincoln Continentals. One hustler from Texas peeled hundred-dollar bills off his money belt. High-rolling customers have talked of helping Butcher do big, big things.

Butcher protests that he isn't naive. "When you're on the edge, you're reaching for business you wouldn't ordinarily reach for," he says. "When you're struggling, you reach for things you shouldn't reach for, and sometimes you get your your fingers snapped on." It's not from a lack of business smarts or stupidity; it's cash flow.

Now Ed Butcher, his wife and their newly hired marketing director, Stu Portnoy, formerly a marketing executive for Little Caesars Pizza, are all on different phones, scrambling for somebody to buy the spurned red car.

"It's amazing how he keeps his sanity," Portnoy says of Butcher. "His attitude is so infectious, you can't help but get excited. But how he can keep his spirits up, I don't know. Anyway, I'm positive that by the end of the week, an order will come through. It's a damn shame. But Ed is a master juggler."

Meanwhile, Butcher has realized he will have to go to the bank today and take money from his own savings to make the payroll and pay the bills. It will not be the first time.

A phone rings again. A Silver Bullet Pulse, sold to Coors and painted in the colors of a can of Coors Light beer, was to be given away at a promotional event in Texas, but has been damaged by a tow truck. It has a cracked windshield which costs $1,200. A new windshield can be sent by Federal Express, along with other parts damaged in the accident, but the shipping bill alone was $950. It's reimbursable, but not soon enough, and it hurts.

At least the farm makes money, Butcher thinks. Some months, 160 acres of corn, wheat and oats are actually carrying the Owosso Motor Car company.

Butcher survived the near death of Owosso's Woodard wrought iron furniture company, where he was a vice president, and was working as a business consultant when he was persuaded to join a group of five investors who united to build the Pulse in July 1984.

In the early days, 42 employees turned out 12 Pulses a week in a 66,000-square-foot factory in Owosso. Production was so steady that the car was offered through Hammacher Schlemmer, the New York mail order house, which featured the Pulse on its catalog cover in 1985.

At first, basics like a heater and reverse gear were optional equipment. In 1989, they were standard, and options included a Pioneer AM/FM cassette stereo, air conditioning, an electric canopy and a cellular telephone. And every Pulse is at least a little different from the previous one because each includes an innovation or little experiment -- whatever occurs to the buyer or the builders. The red #328, for example, has a new electric canopy retraction system and lots of extra lights.

But soon after the company began, a marketing group filed a panoramic lawsuit challenging the very right of Owosso Motor to do business, drying up its access to capitol and forcing it to seek protection under Chapter 11 of the federal bankruptcy code. The five other partners left, but Ed Butcher stuck it out, and the suit was latter settled out of court.

Since October 1986, when the operation moved into Butcher's barn, and with rare exceptions, Butcher and his tiny staff managed to make and sell one Pulse every week. It became a mission, an act of defiance against timid bankers and a system that seems to conspire against the little guy. He says his company's debts totaled $450,000. He has tried and failed to get bank loans for the company. He has turned to a Livonia-based venture capitol group, but so far, nothing has happened.

"If I had $350,000 in the bank, well, there's stability," Butcher says. "I don't have it. And now I'm going farther into a financial hole."

He predicts a pending reorganization plan to repay debts under Chapter 11 will make it easier to attract investors, dealers, even bank financing. But his optimism seems to be yellowing a bit.

"This thing is precarious because it's so vulnerable, and cash flow is so critical. It's just crisis, crisis, crisis," Butcher says. "I do live a pretty stressful life."

For Butcher, the Pulse is a dream, a headache and the source of his self-esteem. The Pulse is the reason he works 90 hours a week and sleeps five hours a night. Because of the Pulse, he worked on his farm -- which other family members tend -- for only two weeks and played only 36 holes of golf -- his favorite sport -- in the past year. For the Pulse, he has refianced his house and farm and dipped into his children's savings accounts, with their uneasy permission.

He added, "There seem to be two kinds of buyers: the youngish motorcycle enthusiasts who buy Pulses to tinker with them, and the colorful, older characters, the vast bulk of the market, who buy a Pulse for its rakish good looks, which seem to appeal not only to Walter Mitty types and pilots, but to every wheeler-dealer and flimflam man between two coasts."

A woman who claimed to be John Davidson's press agent wanted to give the entertainer a Pulse as a birthday gift, until she realized Butcher actually expected to get paid for the car.

Two Pulses were shipped to Universal Studios in Hollywood for the movie "Back to the Future: Part II," filmed by Steven Spielberg's production company. How they humped to finish those cars on time, with the assurance that somebody would probably want to buy one. But nobody has. It was in the movie, but only a few seconds.

Butcher also recalled a phone call in the middle of the night by some guy he had never talked to before, a guy from New Jersey, who said he had been promised a Pulse dealership and was tired of waiting and would Butcher like to talk to his friend, some gorilla who got on the line and threatened Butcher's life while he lay in bed in a farmhouse in rural Michigan. But nothing ever came of it.

What attracts such people to the Pulse is that the Pulse attracts everybody else.

Imagine driving a Pulse to work. Imagine driving it to a dentist's appointment. You wouldn't do it a second time. The Pulse is not really a form of transportation, it is a crowd generator. A gawk evoker. An aphrodisiac.

"I'd like to have driven up to the Oscar ceremony in one of these things. I would have gotten in," says Butcher, who has never been to the Oscars and usually drives a Buick sedan.

"There's no place you can't go with this thing, I'm telling you. You can park it on the sidewalks and the cops will just grin," Butcher said.

Consequently, the car chiefly attracts people who at least want to look like they have egos big enough to handle all the attention. One buyer told Sue Butcher he had never had any friends until he acquired a Pulse.

Women don't buy nearly as many Pulses as do men, Butcher says. Many women are put off by the peculiarities of the motorcycle-style clutch. But that's not to say women don't appreciate the Pulse.

Men who own Pulses report frequent propositions by strange women. Butcher says one young woman climbed onto an outrigger and begged for a ride at an air show in Michigan. And he once watched as a young woman mooned a Pulse owner who refused to give her a ride.

Rich Binning, a 54 year old Chicago entrepreneur, has owned a Pulse for only a few months. He bought it to help promote his company, Micro-Cut, which uses laser beams to cut plastics for industrial and medical uses.

"Driving the Pulse, I have been propositioned five times, and not by professionals -- by young ladies on the promiscuous side," Binning says. "I think it's neat. I'm not as heavy as Butcher, and I'm no Tom Selleck, either, but I've never had women throw themselves at my feet before."

John Russell, a High Point, N.C. photographer who also owns a Lotus and Ferrari, says neither car causes the sensation the Pulse does. He made the mistake of driving his to the grocery store one day and spent so much time explaining it to the crowd it attracted that his ice cream practically melted on the seat.

If words were nickels, the Butchers would be rich. For Ed and Sue Butcher publicity has never been a problem. Newspaper feature writers from California to Conecticut have found these strange cars irresistible fodder including magazines ranging from People to Business Week to AutoWeek to GQ have done articles. Pulses have appeared in a futuristic commercial for New York Life Insurance, and on "Beyond Tomorrow," a Fox Network show about the future, the narrator drives a Pulse.

Pulses also have been used to deliver Domino's Pizza in Maryland. The Chicago man, Binning, bought a second Pulse for use by Action Against Intoxicated Motorists of Chicago, formed to crusade against drunk drivers. The results were spectacular. "We have passed out more literature using the AAIM-Mobile Pulse, in three weeks, than in all of the past four years, including 27 parades, and 17 visits to high schools."

Below Ed Butcher in Owosso parade. Sign says 'Autocycle by Weekleys RV'. Don Weekley was the local 3 state dealer.

But as the Butchers know too well, publicity and customer satisfaction don't pay the bills.

In the basement of their home, Sue Butcher struggles to make a cranky database program work on the company's new off-brand IBM compatible computer. She has wedged it into a space cleared on her sewing table, beneath the Danielle Steele novels on the bookshelf, right across from the washer, dryer and deep freeze. Then in a rare moment, Sue lets her mind wander. Way back. Back to the gravel pit.

When she and Ed were young, the gravel pit, with an artificial lake, was the center of teenage social life and the school for some of life's important lessons.

Ed Butcher made the hardest decision of his teen years when he opted to help his dad bring in the harvest instead of helping his friends build a diving board at the gravel pit. Today, he believes that decision helped shape his priorities.

It was at the gravel pit that Sue first met Ed Butcher. They were in the eighth grade, it was winter, and they joined a pack of kids playing Red Rover on ice skates.

"It was just one of those things." she says, giggling softly. "He was even kind of obnoxious, not afraid of people. Me, I'm the timid and shy one."

Their courtship continued through high school. It was stormy at times. One of their biggest fights occurred the week of the senior prom, so they each took somebody else to the dance. But early the next morning, Sue awoke to find Ed Butcher, still dressed in his tuxedo, milking her father's cows. They married at age 20. That was 22 years ago.

Guy Chunko, 29, who welds the frames together, puts down his torch and wipes a hand across his forehead, "Ed has been real good about paying us," he says. "Maybe sometimes he'll say, 'Let's wait until Tuesday' -- we usually get paid on Friday -- but he is real good about paying us when he says he will."

Chunko, who welded lawn furniture for Butcher years before at Woodard Furniture Co. in Owosso, says he doesn't envy people who work at General Motors, even though they make more money. GM assembly workers are not craftsmen like the workers at Owosso Motors, he says. They can't build one fourth of a car each week. And they certainly don't have the chance to WOW the young women at stoplights during Pulse test drives.

"Sure", Chunko says, "I've known a dozen guys who worked over there. One day they're making $600 a week, the next day they're on welfare." There's something to be said for consistency, however precarious.

"You have your bad days and your good days," Larry Butcher recalls, "I didn't know if I would have a job in six months or I would be part of some $2 million company."

There were so many "IF ONLYS" about Owosso Motors: If only the bankruptcy court approves Owosso Motors' reorganization plan, then it can get bank money. If only independent entrepreneurs would invest, then it could have some working capital. If only Owosso Motors had some dealers, then someone else could handle the selling and assume some of the risks. If only Owosso Motors could sell the red car, then it could build another.

And then there was the case of the young Japanese man whose father ran a highly successful seaweed harvesting company. The young man, a student in the United States, visited the pole barn and was so wildly enthusiastic about the car he offered to buy 1,000 for sale in Japan. That seemed like a project that could take years, but would result in $15 million in sales -- if the Japanese Ministry of Transportation ever agreed to allow the Pulse on the roads.

"This company had the potential to be an $80 million company," said Butcher. "People ask, 'What makes you think you can take on the auto industry?' Heck, I'm not taking on the auto industry. There are 32 million vehicles a year sold in this country. I'm talking about manufacturing 5,000 a year. That's as many Fieros as they make in a day."

After money, what the company needed most was a network of, say, 20 dealers according to Butcher and Portnoy. But it would take more money, more cars and a more comprehensive blueprint for success.

Jim Howell, president of the Planning Group Inc., a Livonia consulting firm helped Butcher seek investors. Howell called him "a fairly typical entrepreneur: He has a tremendous amount of energy and dedication, and his business is like his child . . . He has put everything he's got into the business, personally and financially . . . and if he succeeds, he will be wealthy."

But he said Butcher's biggest fault was not that he's got too little money but that he has not been enough of a strategist. "Companies aren't undercapitalized; that's just a symptom," Howell says. "Businesses really fail for lack of effective planning."

Butcher's creditors anxiously await his return to solvency. John Woodbury, president of Woodbury Sheet Metal of Owosso, sells steel parts to the company only COD now; Butcher owes him more than $5,000 for parts bought just before the bankruptcy.

"I'm a relative of his, you know," Woodbury says. "His wife is my cousin. And I always thought he would treat me pretty square, but I'm not so sure he did."

Still, Woodbury respects Butcher's stamina. "I think he's been through the mill enough," Woodbury says. "It's the tough things that make you hard. He started out naive, he's had to scramble for financing and through bankruptcy, and he's kept his head above water a lot longer than I would have thought. I would have given up long ago."

David Vaughn, one of Butcher's original partners, says he had to sell Vaun-Garde, his auto supply company, partly to help pay Owosso Motors debts.

But Vaughn insists he feels no animosity toward Butcher, although the two have had plenty of arguments.

"Ed is one of the entrepreneurial greats," says Vaughn. "He is full of blood and guts. He's tough, you know. And my God, I hope he's going to make it."

Butcher was convinced there was a market for 5,000 Pulses a year. "The next generation won't have motorcycle engines, though. Instead, they will probably be fitted with 1.3-liter car engines, the size found in a Ford Festiva," Butcher said. And an automatic transmission was in the works. "That would open up the car to a whole new sort of consumer, the 80 percent of all car buyers who prefer not to shift gears," he said.

But some Pulse owners, who love best the novelty of the Pulse, have mixed emotions about all that.

"For Ed's sake, I hope people buy it," Binning says. "For mine I hope they don't."

A week after the red Pulse #328 falls through, Ed Butcher hears from a dentist near Detroit who had seemed enthusiastic about buying the car. But now he has changed his mind. Oh, well. There are surely other prospects.

In the end, the Chicago entrepreneur who already owns two Pulses arranges to buy a third -- the misbegotten red one -- for his anti-drunk-driving crusade.

It is repainted white, and tail fins are added, to make it look exactly like the other AAIM-Mobile which has been so successful. And Butcher, who had worried he would have to unload the car at bargain basement rates, is relieved that Binning has paid him full retail price. And this check has cleared. There's money in the bank again.

Time to build Pulse #329.

But surely it can't always be so hand to mouth around here. Surely someday, the bumpy ride of the little Owosso Motor Car Co. will be smoother.

As Butcher was blasting down Six Mile Creek Road in a customer's Pulse a few weeks ago, he remembered something he heard in a movie: "The sun don't ever shine on the same dog's ass every day."

He said it out loud. and then he laughed.

Chuck Furgason owned Pulse #328 at one time. He said that the canopy on that Pulse didn't appear to be any taller than other Pulses and the gauges were still behind the steering wheel and difficult to see.